Anthropology, at its very core, is built upon the practice of ethnography. For decades, it has been celebrated as the heart of the discipline, the pulse that keeps anthropology distinct from other social sciences. Ethnography is not just a method; it is a lived experience, an immersion into the field, and the transformative process through which anthropologists learn to see the world through the eyes of others. This is why the fourth year of anthropology degrees traditionally culminates in the thesis: a capstone project where theory, methods, and ethics converge into a single act of fieldwork.

What happens when the thesis is made optional?

Increasingly, universities are allowing anthropology students to replace a thesis with additional coursework. At first glance, this seems like a gesture of flexibility. After all, not every student aims to become a researcher. Some aspire to careers in NGOs, development agencies, policy-making, or education, where research may seem less relevant. Giving them the choice to bypass fieldwork in favor of courses appears to democratize the degree. Yet, beneath this surface, a troubling paradox emerges.

The Curriculum Contradiction

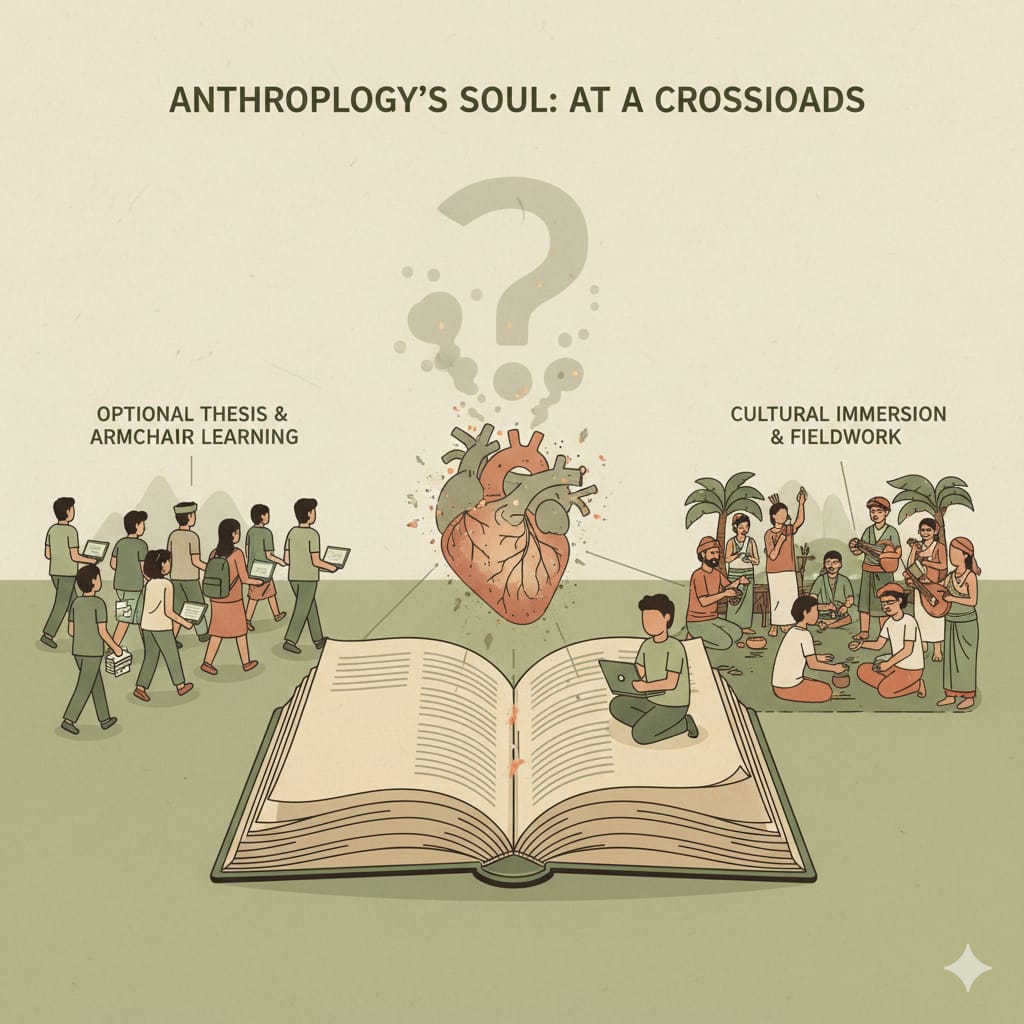

For three and a half years, teachers train students in the art of anthropology. They learn how to ask ethnographic questions, how to employ qualitative methods, and how to ethically navigate the complexities of cultural life. The curriculum itself prepares them for the moment they step into the field. And yet, when that moment arrives, when students finally get the chance to conduct their own ethnography, the system provides an exit door. Instead of stepping into the field, many understandably opt for the easier path: two additional courses instead of months of research and writing. The very structure of the curriculum, then, undermines its own purpose.

The Easy Route Bias

Let’s be honest: most students will choose convenience. Courses, no matter how rigorous, are finite, predictable, and far less demanding than the unpredictable labor of fieldwork. A thesis requires not only academic skill but also emotional resilience, cultural sensitivity, and personal investment. By offering a course-based alternative, universities unintentionally incentivize avoidance of the very thing that anthropology claims as its defining practice.

What’s at Stake for Anthropology?

This is not a trivial matter. Anthropology without ethnography risks becoming anthropology without a heart. If graduates complete their degrees without ever conducting fieldwork for a thesis, what distinguishes them from graduates of sociology, political science, or cultural studies? What ensures anthropology remains a discipline rooted in lived realities rather than abstract theories? The danger is not merely academic; it is existential. Without ethnography, anthropology risks losing the very thing that sets it apart.

Fieldwork as Universal Experience

Here’s the bigger issue: in almost every field, professional life demands experience on the ground. A marketing professional must test campaigns in real markets, a business analyst must work with clients, and NGO workers must immerse themselves in the communities they aim to serve. Why should anthropology be different? For anthropologists like Franz Boas, fieldwork is not just desirable; it is essential. Whether working in policy, advocacy, or research, you cannot speak for people without first listening to them. You cannot decide on matters like child labor, working-class rights, or community health by sitting in a library. You must sit with the people, understand their lived struggles, and learn directly from them, which Clifford Geertz called “Thick Description.” Without this first-hand experience, the very skills anthropology prides itself on, communication, empathy, cultural sensitivity, and critical advocacy, are left underdeveloped.

Why Universities Still Do It

To be fair, universities argue that optional theses provide inclusivity. Not every student envisions themselves as a fieldworker. Some are more interested in applied tracks, others in theoretical explorations. The optional thesis model, then, appears to cater to diverse career paths. But this inclusivity steeply costs anthropology: it dilutes the discipline’s identity and leaves it vulnerable to being subsumed by broader social sciences.

The Critical Question on Thesis Choice

The real question isn’t whether flexibility is inherently good or bad; it’s whether that flexibility should come at the cost of anthropology’s very soul. After more than a century of struggle to establish itself as a discipline rooted in lived realities, anthropology now risks sliding back toward what Franz Boas once dismissed as:

“Armchair anthropology; the mere cooking of data without ever tasting life in the field.”

– Franz Boas

If anthropology prides itself on ethnographic sensibility, on the commitment to seeing, listening, and engaging with life as it is lived, then how can students graduate without at least one genuine immersion in the field?

“Ethnography is not just a method; it is, in Clifford Geertz’s words, a ‘thick description’ of human existence; a way of making meaning out of the ordinary that reveals the extraordinary.”

The fourth-year thesis, even if imperfect, is precisely that defining moment when students finally put theory into practice and discover the heartbeat of anthropology in lived encounters.

Conclusion: A Call to Reconsider Thesis

Making the thesis optional may appear student-friendly, but in reality, it creates a contradiction that weakens anthropology’s core. The discipline must ask itself: do we want graduates who have merely read about ethnography, or graduates who have lived it? The answer to this question will determine not only the future of anthropology education but the future of anthropology itself.

By turning the thesis into a choice rather than a necessity, universities risk training anthropologists who never actually become anthropologists. And that, perhaps, is the greatest paradox of all.